Bound for Botany Bay

The early years of the Australian colony

Former Prime Minister Tony Abbott once infamously and erroneously stated that there had been “nothing but bush” in Sydney Cove when the First Fleet arrived.1 Of course, there were thousands of people living in and around Sydney Cove; as Lieutenant Watkin Tench, whose narrative of the journey, The Expedition to Botany Bay, is one of Australia’s foundation books, noted, the country was likely much more populated than Lieutenant Cook had thought when he had mapped the coastline in 1770.2 These people had sophisticated cultural practices, extensive trade networks, and deep ties to the Country they had shaped with fire3 into a landscape that Arthur Bowes Smyth, ship’s surgeon on the Lady Penrhyn, described:

…the finest terraces, lawns and grottos with distinct plantations of the tallest and most stately trees I ever saw in any noble man’s gardens in England cannot exceed in beauty those which nature now presented to our view.4

When the last of the eleven ships which made up the First Fleet sailed into Botany Bay on January 20, 1788, their passengers must have felt considerable relief that their thirty-six-week journey was finally at an end. The fleet had lost only forty-eight souls on the journey — one marine, one marine's wife, one marine's child, thirty-six male convicts, four female convicts, and five children of convicts5 — a remarkable outcome considering how poorly provisioned the fleet was. Lieutenant Tench recorded that they were not allowed portable soup, wheat, or pickled vegetables, and provided only an inadequate quantity of essence of malt with which to prevent scurvy, so the successful completion of the voyage was remarkable indeed.6

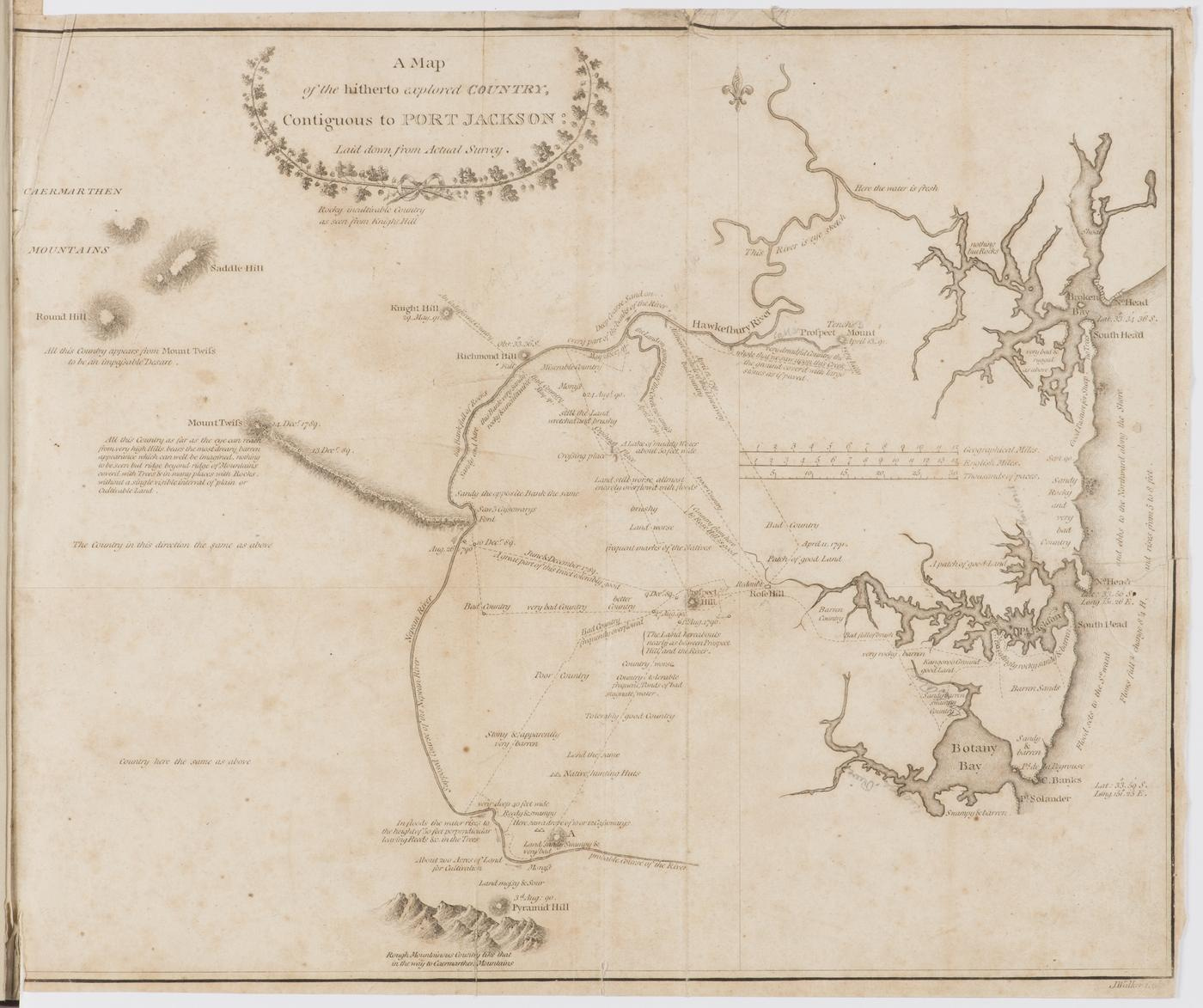

The fleet was but the first in an ambitious plan to establish a penal colony to relieve Britain’s overflowing prisons and hulks. Britain had previously transported prisoners to its American colonies, but the loss of the War of Independence meant a new destination was needed. Botanist Joseph Banks, who had travelled with Lieutenant Cook in his exploration and mapping of the east coast of the land they called “New Holland” in 1770, recommended Botany Bay. Cook had already claimed the land for Britain and a colony would also stake a claim for the crown in the Pacific and prevent rivals from establishing a footing.7 Indeed, there were two French ships conducting a scientific survey of Botany Bay when the Fleet arrived.

Botany Bay proved unsuitable for settlement due to its lack of fresh water and exposure to the sea and strong southeast winds, and the decision was made to relocate the new settlement to a bay further north that Lieutenant Cook had named Port Jackson. The new settlement was named Sydney Cove, in honour of Thomas Townshend, 1st Viscount Sydney, the British Home Secretary. The convicts came ashore January 27, 1788, and on February 7, Captain Arthur Phillip read aloud his commission, proclaiming the colony of New South Wales and himself as Governor. In March Phillip sent Lieutenant Philip Gidley King to Norfolk Island, approximately 1500 kilometres to the north-east to secure possession of it and its resources, which included flax and pines for ship sails and masts.8 This decision would later become significant to the survival of the fledgling New South Wales colony.

The fleet had brought provisions for two years to help the colony become established but beyond that the colonists were expected to fend for themselves. Stock animals included one stallion, two bulls, nineteen goats, five rabbits, thirty-five ducks, three mares, five cows, forty-nine hogs, eighteen turkeys, one hundred and twenty-two fowls, three colts, twenty-nine sheep, twenty-five pigs, twenty-nine geese and eighty-seven chickens.9 Colonists survived on government rations of salt meat, flour or biscuit, peas and rice, which were supplemented with wheat, maize, potatoes, turnips and cabbages farmed in community gardens. They were also encouraged to establish their own vegetable plots and were provided seed and tools and given time off to tend them. They supplemented what they could grow with native plants like samphire, wild sage, purslane and cabbage palm.10

It was soon established that the sandy soil around Sydney Cove could not support European crops, so farming moved to more fertile soils in Parramatta, about twenty-five kilometres to the west along the river. Colonists also hunted native animals, with large hauls like kangaroo and net-caught fish remaining the property of the government, while colonists were allowed to keep smaller catches like possums, shellfish, eels, and birds. Of course, the larger, stationary population of people using European extractive farming methods rather than renewable Indigenous methods soon exhausted the native resources. One example is the cabbage palm, of which in July 1788 it was reported “we have not left one within a dozen of miles of us.”11

Colonists soon found it difficult to grow and hunt enough food and stores were depleting. The ship Supply made a trip in May to Lord Howe Island to catch sea turtle but returned empty. In June, six of the cattle the fleet had brought strayed into the bush and were lost.12 They were not found again until 1795, having crossed the Nepean River and increased into several herds numbering about one hundred.13 Phillip sent the Sirius to the Cape of Good Hope to procure supplies in October, but the Guardian, bringing those provisions as part of the Second Fleet, hit an iceberg in December 1789 and was forced back to the Cape where it was wrecked.

Phillip responded to growing concerns about starvation by reducing government rations and sending even more convicts to the settlement on Norfolk Island in March 1790. The convicts and officers where landed but the Sirius was wrecked off the coast of Norfolk Island in the process. In April the Supply was sent to Batavia in the Dutch East Indies for emergency supplies and did not return until September.14 The six ships of the Second Fleet began to arrive in the meantime, in June 1790, with few provisions and hundreds of sick and dying; indeed 124 died soon after landing. The colony’s Chaplain Reverend Richard Johnson described the survivors thus:

the misery I saw amongst them is indescribable ... their heads, bodies, clothes, blankets, were all full of lice. They were wretched, naked, filthy, dirty, lousy, and many of them utterly unable to stand, to creep, or even to stir hand or foot.15

The colony was close to starvation before the eleven ships of the Third Fleet began to arrive in July 1791. The supplies saved the colonists and made officials in London aware of the desperate need for experienced farmers and labourers in New South Wales.16

Prime Minister Tony Abbott describes Sydney as 'nothing but bush' before First Fleet arrived in 1788, ABC News, 2014, https://www.abc.net.au/news/2014-11-14/abbot-describes-1778-australia-as-nothing-but-bush/5892608.

Watkin Tench, The Expedition to Botany Bay, 1789, in Watkin Tench, 1788, edited by Tim Flannery, Text Classics, 2012, p 40.

Bill Gammage, The Biggest Estate on Earth, 2012, Allen and Unwin.

Arthur Bowes Smyth, Journal of Arthur Bowes Smyth, 1787, p 131, held by the National Library of Australia.

John White, Journal of a Voyage to New South Wales [Port Jackson], 1790, privately published. Project Gutenberg.

Watkin Tench, The Expedition to Botany Bay, 1789, p 37.

Museums of History New South Wales, First Fleet Ships, 2025, blog, https://mhnsw.au/stories/first-fleet-ships/first-fleet-ships/.

Jacqui Newling, Phillip’s Table: Food in the Early Sydney Settlement, 2018, Dictionary of Sydney, State Library of New South Wales, https://dictionaryofsydney.org/entry/phillips_table_food_in_the_early_sydney_settlement.

An Account of the English Colony in New South Wales, with Remarks on the Dispositions, Customs, Manners etc. of the Native Inhabitants of that Country by David Collins Esq. late Judge Advocate and Secretary of the Colony, London, 1798. This account was published after Collins returned to England in 1797. He created this list in May 1788, State Library New South Wales, https://www.sl.nsw.gov.au/learning/food-colony/animals-they-brought-them.

Jacqui Newling, Phillip’s Table: Food in the Early Sydney Settlement, 2018, Dictionary of Sydney, State Library of New South Wales, https://dictionaryofsydney.org/entry/phillips_table_food_in_the_early_sydney_settlement.

James Campbell, Letter from Captain James Campbell to Lord Ducie, 12 July 1788, State Library of New South Wales; Jacqui Newling, Phillip’s Table: Food in the Early Sydney Settlement, 2018, Dictionary of Sydney.

Watkin Tench, The Expedition to Botany Bay, 1789, p 65, 67.

Cheryl Timbery, First Fleet Cattle, 2013, First Fleet Fellowship Victoria, https://firstfleetfellowship.org.au/library/first-fleet-cattle/.

Wikipedia contributors, First Fleet, Wikipedia: The Free Encyclopedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=First_Fleet&oldid=1298233962.

Letters from the Rev. Richard Johnson to Henry Fricker, 30 May 1787-10 Aug. 1797, with associated items, ca. 1888, Mitchell Library, cited in Steve Tong, Richard Johnson: Chaplain Under Fire, 2023, Australian Church Record, https://www.australianchurchrecord.net/richard-johnson/.

Life on the Land, State Library of New South Wales, https://www2.sl.nsw.gov.au/archive/discover_collections/history_nation/agriculture/life/index.html.

Thank you, Jean, for such a detailed account of those first difficult years after the arrival of the First Fleet. What struck me most was how precarious life became so quickly, with the colony relying on meagre rations, failed crops, and emergency voyages for supplies. I also found it fascinating that the six cattle lost in 1788 were not found again until 1795, by which time they had multiplied into herds of about one hundred. It is a vivid reminder of how fragile the settlement was in its early years, and how much improvisation and endurance were required simply to survive.

I think my own fascination with Australian history began with that lost herd of cattle. I remember reading about the First Fleet and the early years of the colony in primary school, and our teacher emphasising, just as you’ve done here, how touch-and-go those first years really were. It made a lasting impression, and your post brought that memory back very clearly.

Thanks Jean. I've always been fascinated with stories of early Australia. Life became unbearable and very dire very quickly for the first settlers as you've shown here.,